iObject

The work presented in the So Far, So Close exhibition collectively titled, iObject, is from The Things We Bring series.

iObject consists of four panels of silkscreen prints, flanked by two wall pieces. In front and to the side of this iteration of the work, are several displays of ceramic pieces and collected artifacts.

As a series The Things We Bring explores how the objects we keep when moving as an immigrant or while living in diaspora are signifiers of culture, ethnicity and history; they become touchstones to our past, of places we no longer inhabit yet want to keep close. Objects we choose with care are the culture bearers, the story tellers. They keep one’s history vibrantly present, while being foundational for the conception of a new life in a new, and often challenging, world.

As part of this series, I’m presenting one visual story of two souvenirs that I brought with me to Minneapolis from Tehran and Jerusalem.

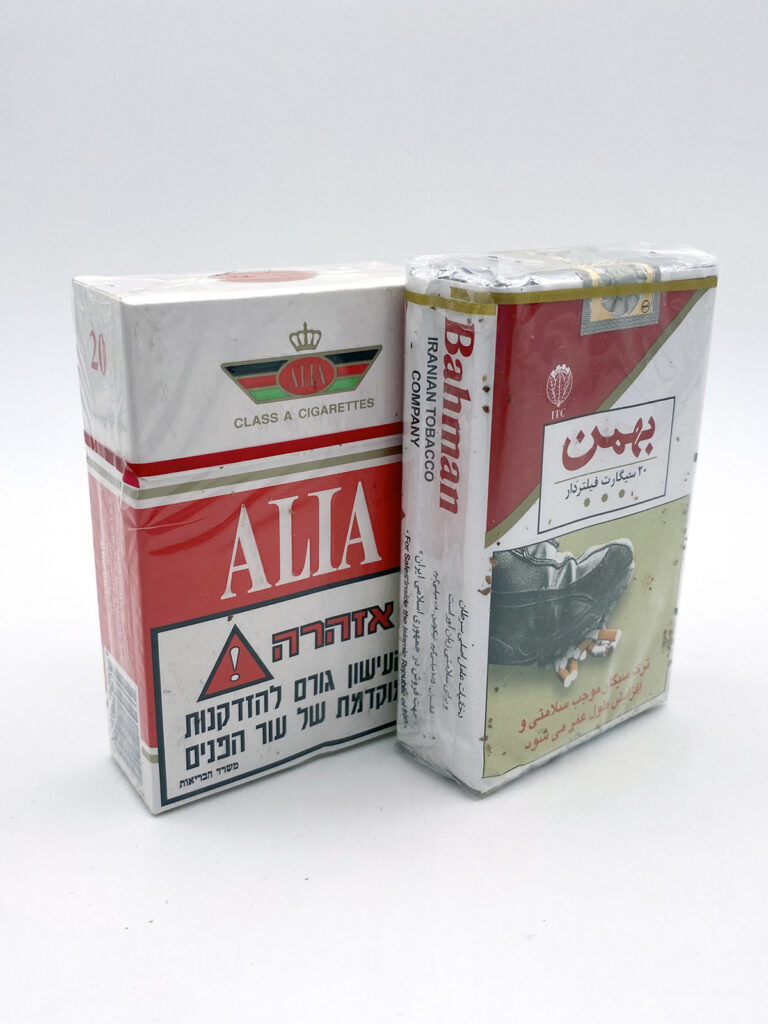

There’s a sense of pride in the word “national”, national heritage, national dish, national flower, etc. In iObject, two seemingly insignificant nationals are the subject of my study: Two ordinary cigarette packs picked up from newsstands in Tehran and Jerusalem.

Tobacco, like any commodity, is layered with associations, meaning and history. Originally native to the Americas and introduced to the old-world through European colonialism, it is now part of a global economy and all that comes with production at that scale. However, the aspect of tobacco that interests me currently is the intersection of brand identity, national identity, and nostalgia, infused with a little irony.

iObject, 2024

installation size varies

part of So Far, So Close exhibition by Katayoun Amjadi, Shirin Goraishi, Ziba Rajabi

Q.arma Building | Q.Underground Gallery | Sept 6-26, 2024

**Download exhibition text in PDF**

Historical Objects

iObject series, 2024

plexiglass, packages of Alia (Jerusalem Cigarette Co.), Bahman (Iran Tobacco Co.)

7 x 7 x 3 ½ in.

Alia is the national cigarette of Palestine, but ironically is sold and is popular in Israel. It is a Palestinian product that has been appropriated by the Israeli population, yet carries the colors of the flag of Palestine. In Arabic Alia means “exalted” or excellent/exceptional. In Hebrew Aliyah is seen as the act of rising, as in ascending to Jerusalem. In modern history, as one of the most basic tenets of Zionism, Aliyah has come to mean the return of the Jews of any nationality to Israel, a “birthright” to gain citizenship in Israel. Alia has the sense of disbursement across multiple countries and cultures, some in direct conflict of contested land.

Bahman is the national cigarette of Iran. In Farsi Bahman means “snow avalanche”, and is also the eleventh month in the Persian calendar, the month of February in the Gregorian calendar. Bahman is the month of the 1979 revolution, toppling Iran’s historical monarchy and replacing it with the present-day Islamic Republic of Iran. In a sense Bahman of 1979 is considered the origin of the Iranian diaspora, as many Iranians migrated to other nations at this time. So at the same time Bahman is the product of the Islamic Republic of Iran, it references the revolution and the consequent dispersal of Iranians into a state of diaspora, and has embedded in it a sense of nostalgia for pre-revolutionary Iran.

Slow Kills – Aliyah & Bahman

iObject series, 2024

CMYK silkscreen print on paper

25 5/8 x 19 5/8 in. each

iObject presents two national flowers along with the cigarette artifacts. Both flowers gather the sense of nationalism and nostalgia, yet each are appropriated by opposite sides of the same conflict.

The tulip has long been a symbol of love, belief and passion, and in Iranian culture it represents the advent of spring as well as the symbol of martyrdom. The tulip’s symbolism in Persian mythology can be traced back to the love story of Shirin & Farhad in sixth-century Iran. The commoner Farhad loved the Princess Shirin, but had nothing to offer but his pure heart. Given a challenge by the king, who abhorred the thought of his daughter marrying someone beneath her noble birth, Farhad labored moving mountains to win Shirin’s love. When it was clear he would complete his task, he was deceived with false news of her death, and threw himself from the cliffs in anguish. According to the legend, scarlet red tulips grew from the land where Farhad’s blood fell.

The central motif of the contemporary Iranian flag depicts four petals of the tulip, combined with a sword representing the five pillars of Islam. Ironically the tulip has more recently been associated with resistance against the current Iranian regime, the same regime that, since 1979, has employed tulip imagery in its own propaganda art. The mythology of the tulip and its appropriation across time, even just within Persian culture, has meant that what it signifies shifts with each iteration from love, to the arrival of spring, from rebirth to the blood of a lover, or the blood of soldiers and innocent civilian martyrs.

The poppy is associated with the grain goddess Demeter, and with its narcotic properties inducing painlessness, slumber or death. The poppy has journeyed across time, history and place as a symbol of the fragility of life, resilience in survival, yet also as the blood of Christ. More recently as a remembrance of those lost in war. In particular it is deeply connected with the trench warfare in the poppy fields of Belgium in World War I. The poppy is also the national flower of Palestine and is associated with a connection to the land, and the bloodshed endured through the Israeli occupation.

Under Boots

iObject series, 2024

earthenware ceramics, iron decal

approx. 14 x 3 x 3 in. each

Bahman Tulipier

iObject series, 2024

earthenware ceramics, gold luster

12 x 7 ½ x 3 ¼ in.